It’s not been a great few weeks for Huawei, the Chinese telecommunications giant and one of Beijing’s “national champion” tech firms. On December 1, Canadian authorities in Vancouver arrested the company’s chief financial officer, Meng Wanzhou, at the behest of the United States. On January 11, news broke that Polish officials had

arrested a Huawei employee on espionage charges. On January 28, the U.S. Justice Department unveiled indictments accusing the company of systematically violating U.S. sanctions against Iran and stealing trade secrets from its U.S. business partner T-Mobile.

The arrest of Meng came just as Washington and Beijing reached a 90-day truce to halt their recent tit-for-tat escalation of tariffs while trade talks continued. This timing—and U.S. President Donald Trump’s suggestion that he could use Meng as a bargaining chip in the negotiations—prompted an outcry from Chinese officials, who painted her arrest as a cynical power play. The response from Beijing was swift: almost immediately after Meng was picked up in Vancouver, China detained two Canadians in what was widely seen as a retaliatory measure. A few weeks later, a third Canadian was

sentenced to death for drug smuggling at a perfunctory court proceeding that was ordered shortly after Meng’s arrest.

Stay informed.

In-depth analysis delivered weekly.

Despite Trump’s reckless tweeting, it’s highly unlikely that Meng’s arrest was timed to give Washington additional leverage over Beijing. She was arrested on charges of fraud connected to sanctions violations, and the U.S. criminal investigation of Huawei

began long before the current round of U.S.-Chinese trade talks. Meng is not a hostage; her detention was a legitimate act of law enforcement.

There is, however, a less transactional and more fundamental connection between the heightened scrutiny of Huawei and Washington’s trade war against Beijing: both stem from the growing tensions and mistrust between Western states and China in matters of technology, economic policy, and national security. Both are driven, in part, by the fear that the Chinese Communist Party’s grip on the country’s private sector means that Chinese companies cannot truly be independent from the Chinese state.

DON'T TRUST BEIJING’S PROCESS

As big data and artificial intelligence advance, the global economy is set to rely more and more on

fifth-generation (5G) mobile networks, which enable large machine-to-machine data flows at ultra-fast speeds. As the world’s largest producer of the telecom equipment needed to operate such networks, Huawei is a colossal player in the global race for 5G dominance. As of late 2018, the company boasted

28 percentof the global market for telecom equipment and had signed more than 25 contracts around the world to deploy its equipment in the 5G networks of the future.

Huawei is a colossal player in the global race for 5G dominance.

But even before the arrest of Huawei’s CFO in December, the company’s global expansion had hit a snag. As early as 2012, the intelligence committee of the U.S. House of Representatives issued a report

warning that Huawei might install “malicious implants” in critical network infrastructure, possibly opening a backdoor for the Chinese government to conduct cyber-espionage and cyberattacks. Such concerns loom even larger in the case of 5G networks that could undergird everything from smart electric grids to autonomous vehicles—not to mention the commercial networks on which U.S. military communications and logistics depend.

Over the past year, the U.S. government began pulling up the drawbridge. In February 2018, U.S. intelligence officials cautioned Americans against buying Huawei phones, and in April, the Pentagon banned the sale of Huawei smartphones on U.S. military bases. In August, Trump signed a bill that restricts the government’s use of technology made by Huawei and another Chinese tech firm, ZTE. Now the Trump administration is

mulling an executive order that would bar all U.S. companies from using Huawei or ZTE equipment.

U.S. officials have taken their

campaign global, and the bid is gaining traction. Last August, Australia barred Huawei from supplying 5G equipment; New Zealand followed suit in November. A month later, the Japanese government

effectively banned Huawei equipment from government contracts, and the country’s main telecom firms announced they would do the same. Canada, Norway, and the United Kingdom are now conducting security reviews of Huawei’s 5G technology, and the French, German, and Polish governments are considering bans of their own. Already, major Western telecoms like the British giant BT and its French counterpart Orange have announced plans to limit or exclude Huawei from their 5G networks.

It is unusual for Western states to march in lockstep in this way, particularly where China is concerned. Just a few years ago, the U.S. allies now lining up to scrutinize China’s largest tech company ignored Washington’s pleas not to join China’s Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank. The current show of unity is all the more striking given that there is no smoking gun incriminating Huawei—no public evidence proving, say, that the company is rigging its hardware or spying on behalf of the Chinese government. To be sure, Huawei has previously been

linked to the theft of intellectual property from Cisco and at least one case of

compromised data involving the African Union headquarters in Ethiopia. The U.S. Justice Department's latest indictments paint a picture of a company that deliberately flouted sanctions law and stole technology from its business partners. But Western governments have yet to present detailed public evidence that Huawei has indeed been spying for China, and the company denies that it does so.

Rather than reacting to specific incidents of cyber-espionage or cyberattack, Western governments are likely driven by a broader concern: the Chinese Communist Party’s deepening control over China’s corporations and other ostensibly nongovernmental institutions. There is good reason to worry. In the United States and most other advanced democracies, there is a clear legal process for the federal government to obtain access to private communications for foreign intelligence purposes, and some American companies have actively resisted government attempts to obtain data in the name of national security. The Chinese system lacks these procedural constraints. The state operates with a

broad conception of national security and in recent years has been tightening its grip on companies and citizens alike. It has strengthened the role of party committees in Chinese companies, rolled out widespread domestic digital surveillance programs, and created an anti-corruption agency that sits above the reach of due process constraints. Against this backdrop, there is a serious risk that, as the 2012 House intelligence report put it, Huawei “would be obligated to cooperate with any request by the Chinese government to use [its] systems or access them for malicious purposes under the guise of state security.”

Chinese officials themselves appear quite willing to blur the line between state and private sector. Huawei’s CFO Meng reportedly held a passport typically issued only to employees of China’s government or state-owned enterprises. And when China detained two Canadians in response to Meng’s arrest, its ambassador to Canada invoked national “

self-defense.” No wonder, then, that many governments no longer trust that there is a meaningful distinction between Huawei and the Chinese government.

THE MEANING OF THE TRADE WAR

Although the diplomatic fallout from the recent arrests has put Huawei’s case into high relief, the company’s close ties to the Chinese party-state are no outlier. As the legal scholars Curtis Milhaupt and Wentong Zheng have

written, a number of major Chinese firms receive preferential treatment through their deep links with the government. Even if nominally private, they benefit from subsidies and insulation from competition in the massive Chinese market. This state-led approach has helped propel the growth of high-tech companies that now rival their Western competitors in areas such as artificial intelligence and quantum computing. But it has also raised hackles in Western capitals, which have complained about a host of unfair practices, including forced technology transfer, intellectual property theft, industrial policy, and various non-tariff barriers, all of which make it harder for foreign firms to compete fairly in key technology sectors. This economic competition matters all the more to states because many of the next-generation technologies being developed by leading tech firms have both civilian and military applications.

These concerns explain why the Trump administration’s goal in trade negotiations with China is much more ambitious than a mere reduction of car tariffs. The United States wants

structural changes to China’s economic policies and its relations with private companies. That is in part why the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States, an executive branch interagency group that reviews the national security implications of foreign investments in U.S. companies, is expanding its scrutiny of Chinese investment in so-called critical technologies. Likewise, Congress has updated the U.S. export control regime to limit the export of certain “emerging and foundational” technologies, which could be

interpreted to cover broad categories such as AI, biotechnology, and microprocessors.

The Trump administration’s goal in trade negotiations with China is more ambitious than a mere reduction of car tariffs.

Washington can take further steps to protect U.S. intellectual property, but there is reason to doubt that the campaign against Huawei or the current trade negotiations will yield anything but symbolic progress on the core question of the party-state’s role in the Chinese economy. For one, there is the matter of political optics. Chinese President Xi Jinping wants to avoid the impression that he is caving in to Washington’s pressure campaign. In a speech last December, he

rejected the notion that outsiders could “dictate to the Chinese people” and committed to maintaining and strengthening the Chinese Communist Party’s leadership “over all tasks.”

The crackdown on Huawei and efforts to protect U.S. technology could also reinforce the view, already taking hold in the party’s politburo, that Trump’s trade war is just one part of a broader effort by the United States to thwart China’s rise—one which requires China to adopt aggressive state policies to achieve technological self-sufficiency. Leaders in Beijing still remember that, just months ago, the U.S. Commerce Department brought the Chinese telecom-equipment company ZTE to the brink of collapse with an

export ban on U.S.-made semiconductors that ZTE uses in its products. The company only avoided this fate—a punishment for its repeated violations of U.S. sanctions against Iran and North Korea—when Trump intervened at the last minute to reverse the penalty. With the prospect of a similar (if less existential) threat looming above Huawei’s operations, those in China who argue for doubling down on a state-directed drive toward self-sufficiency have new ammunition for their case.

Still, there are some within China who think otherwise. Many Chinese

elites, particularly in the academy, think that Xi has

overreached both in his foreign policy and in his domestic consolidation of power. A number of

prominent Chinese analysts have

argued that the market-opening reforms demanded by the United States are in line with China’s long-term goal of moving up the value chain and developing an innovation-based economy driven by fair market competition. Despite the advances in China’s tech sector, they argue, its state-led approach and tightened political control have spawned bureaucratic sclerosis, waste, and inefficient management.

It is possible, though far from preordained, that this friction—both domestic and international—may begin to shift Chinese leaders’ calculus. News that China’s top planning agency will

rewrite its Made in China 2025 industrial strategy to allow for more foreign competition is a welcome start, but the true test will be whether such promises are followed through. Structural Chinese reforms need not be framed as concessions to U.S. pressure, as they are largely consistent with years of official Chinese rhetoric about deepening the country’s process of opening and reform. China’s slowing growth, enormous debt overhang, rising labor costs, and aging population make such an overhaul more urgent than ever.

DON’T BOO. ACT.

The United States, for its part, should heed the difference between competing and merely whining. On the technological front, this means recognizing that Huawei will continue to be a major player in the global market for 5G infrastructure. Washington must move ahead swiftly on

regulatory reforms to incentivize private-sector investment in the United States’ own 5G infrastructure. It must work with like-minded allies and partners to address cybersecurity vulnerabilities and protect strategically sensitive technologies without undermining the innovation ecosystem that gives rise to their development.

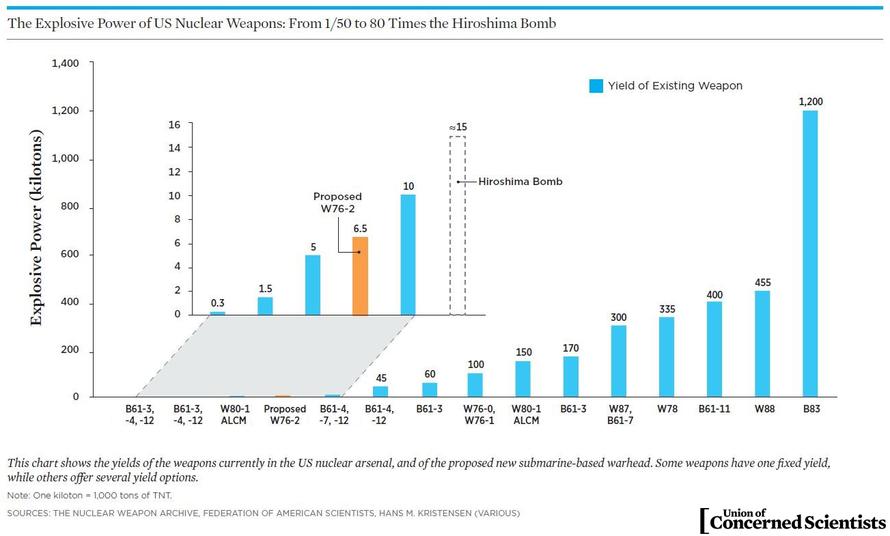

We’re just going to trust that you recognize this is “just a little nuclear weapon” and won’t retaliate with all you’ve got.

We’re just going to trust that you recognize this is “just a little nuclear weapon” and won’t retaliate with all you’ve got.